A Brief History of Trauma and Mental Health

Exposure to trauma is and always has been part of the human condition, whether it be collective experiences, such as attacks by wild animals, storms, wars, and terrorism, or more individual or insidious, as with illness, addictions, assault, bereavement, and loneliness. The impact on mental health is now clear, yet, for thousands of years, it was often believed that mental illness was created by evil spirits entering and taking over the body, or due to taboos being violated or rituals neglected, thereby resulting in mental disorders. Records from Egypt, written around 5000 years ago, describe three kinds of healers: physicians, who treated the physical body; priests, who cared for spiritual health; and sorcerers, who dealt with the supernatural. Such beliefs persisted well into the middle ages, when people with mental illnesses were often viewed as demonically possessed or accused of being witches; these unfortunates were usually cast out of their homes and villages to fend for themselves. Various physicians believed that patients suffered from physiological imbalances which created ‘unusual behaviours’ and conditions now known to be epilepsy, personality disorders, anxieties, phobias, eating disorders, and depression. The luckier patients managed to avoid ‘treatments’, which might consist of exorcisms, forced starvation, invasive surgery to the skull, and erroneous medications, none of which did anything to help those affected. Several cultures believed that mental illness was caused by the passing phases of the moon, which gave rise to the term ‘lunacy’. When people experienced trauma, either as an individual event or multiple occurrences, they were sometimes said to be cursed - tainted by bad luck; a long-established expression among sailors for shipwreck survivors was the term, ‘Jonah’, which referred to a sailor or a passenger whose presence on board had brought bad luck in the past and endangered future trips. The term was later extended to mean any person who was considered to have brought bad luck to a situation. Sadly, few people experiencing such trauma resulting in mental illness or other conditions affecting the mind could expect sympathy or understanding from those around them.

As centuries passed, people with mental illnesses in Britain were often subjected to additional harms and discrimination. At some time between 1255 and 1290, the Prerogative of the King Act, De Praerogativa Regis, ensured that the reigning monarch was given custody of the lands of ‘natural fools’ and wardship of the property of the ‘insane’. Until the English Civil War and interregnum, when normal government was suspended during the 1640s, all land reverted to the king upon the chief tenant's death, though it could be reclaimed by any lawful heir on payment of a fee. The King's Officers, ‘Escheators’, regulated these matters and sometimes held inquisitions to determine if a land holder was a lunatic, an imbecile, or an idiot.

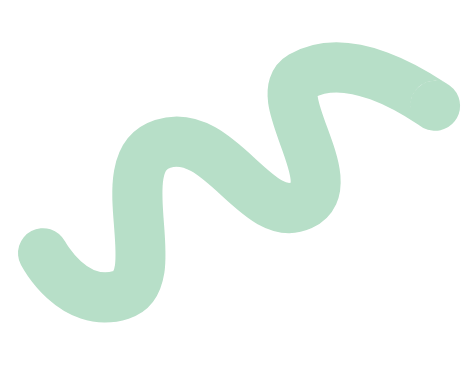

It was during this period, around 1377, that Bethlehem Hospital was founded within the Priory of St Mary of Bethlehem, London. The hospital was the first to house ‘distracted persons’ but became notorious for its callous, often cruel treatment of patients. You may know Bethlehem Hospital under its more infamous nickname, ‘Bedlam’. By the 1600s, it was common practise either to keep those labelled ‘insane’ in the family home, or to put them into a ‘madhouse, the latter being a private house whose proprietor was paid to simply detain the residents; he or she was not medically trained and they ran their establishment as a commercial concern only, with little or no medical involvement. This led to two forms of abuse - the first was that ‘legitimately’ insane people were held in atrocious conditions, and the second was the imprisonment of individuals who were falsely claimed to be insane. At this stage, there was no legislation or responsibility to regulate the incarceration of anyone other than a Chancery lunatic (usually a person from a wealthy family), or a pauper; there was only a vaguely defined common law power to ‘confine a person disordered in mind, who seems disposed to do mischief to himself, or to another person’. Unsurprisingly, many madhouses were subject to public scandals, with proprietors and staff accused of horrific abuses, malpractices, and mistreatment. Cases of ‘wrongful confinement’ became a public concern and a Parliamentary committee investigation, in 1763, uncovered a high number of sane people who had been sent into private asylums by relatives, or people who had once been considered ‘friends’, usually for financial or social benefit. Of the more disturbing cases was a wife imprisoned by her husband for lacking passion and acting 'indifferently' within the bedroom, and two young girls who were locked away because their parents did not approve of their boyfriends. Another woman had been committed to a madhouse solely on the word of her husband, who paid two guineas a month for her board; she was unable to leave the house or communicate with anybody outside it. Proprietors and families sometimes obtained the services of an agent to arrange admissions; one agent freely admitted that he had not committed a single insane person to the house in the past six years. No-one who would pay for this ‘service’ was turned away, despite the fact that no physicians declared new arrivals as insane; notably, few registers were kept of the names of inmates.

These concerns, and many others, resulted in 1774 Act for Regulating Private Madhouses, which aimed to limit the number of patients who could be admitted into madhouses, created licenses and regular inspections for madhouse proprietors, and made it necessary to obtain medical certification for the incarceration of lunatics. Theoretically, this legislation provided for improvements but its practical impact was limited. In Scotland, the first lunacy legislation was the 1815 Act to Regulate Madhouses (Scotland), which also made provision for fee paying patients that were confined in institutions run by private individuals for profit.

The aims of the Scottish 1815 Act were similar to those of the 1774 Act. The later Parliamentary Committee on Madhouses discovered that obtaining a license was little more than a formality, and there was no evidence to suggest that a licence was ever refused. In reality, the first Madhouses Acts served not to eradicate the abuses rather than to license and permit the existing cruelties of the status quo.

Caricature of Bethlem Hospital; satirises politicians as lunatics. By Thomas Rowlandson, 1789.

By this time, more doctors were less inclined to consider demonic possession and instead believed that physical health issues were the result of physical illness, and they prioritised treatments that focused on fixing the physical symptoms; this might involve advising patients to change their diets or use medications if they experienced regular stomach ache, etc. However, patients deemed to be experiencing mental ill-health, particularly those from poor financial backgrounds, continued to be ‘removed from society’ and placed in asylums for the insane well into the 20th century. These poor wretches included alcoholics, people with learning disabilities, former soldiers suffering from shell-shock, and young unmarried mothers – girls whose sexual behaviour was said to be the result of mental depravity, despite it being known that they had been raped or taken advantage of by elders or ‘superiors’. Social isolation in psychiatric hospitals and insane asylums was thereby also used as a form of punishment for people not necessarily affected by poor mental health issues.

In 1815, the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh and the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow appointed doctors to inspect all asylums (both public and private), along with the Sheriff of the county, and to report on these inspections. From 1815 to 1841, these reports appeared in the College minute books. These reports described asylums during the early period in the development of psychiatry and the treatment of mental illness, not only in the larger public institutions, but also in the smaller, private asylums. They also highlighted the role of the inspectors and their attempts to improve conditions in asylums, along with recording patients’ names, general conditions, cleanliness and ventilation, and the number of patients, both male and female. The Inspectors also assessed how patients were treated, and whether any patients were under restraint or placed in isolation. Inspectors often highlighted areas for improvement, such as for accurate records to be kept at each asylum, including admission and dismissal books, and case books with notes to be kept for each patient; some inspectors recommended lower beds for patients with epilepsy, or commented on the ability or otherwise of staff and managers. Overall, the reports from that period suggest that inspectors found conditions within asylums to be poor and left much to be desired. This conclusion was supported by the 1857 Scottish Lunacy Commission inquiry which found that the official surveillance of mental health institutions ‘remained at best variable and at worst simply inadequate’. It recommended the formation of a Scottish Lunacy Board to address the deficits.

Illustration of the Royal Asylum at Montrose from Richard Poole’s book, published in 1841.

In Scotland, the late 19th century was a time of major restructuring that eventually led to the formation of a unique Scottish system of care for the mentally ill. When the inadequacy of asylum accommodation and a lack of supervision became a concern there, the Lunacy Act (Scotland), 1857, placed the responsibility for the well-being of mental patients in the hands of the central government. Here, the General Board of Commissioners in Lunacy for Scotland was established to oversee the requirements for patients, though the Board’s powers were limited to advisory-only in cases where patients were supported by their own families without public assistance.

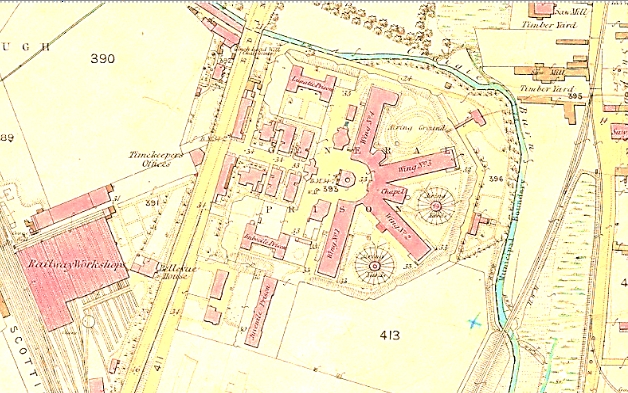

Perth Prison, 19th Century

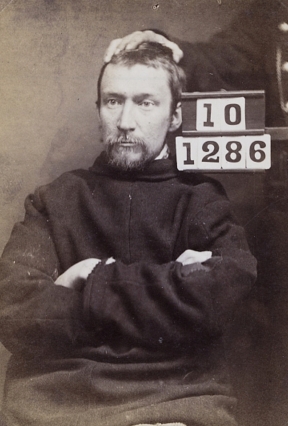

In the Victorian era, much as now, a high proportion of prisoners lived with mental disorders. The Prisons (Scotland) Act (1844) defined criminal lunatics as ‘insane persons charged with serious offences’, and some prisons treated those inmates differently to those in the general population. For example, from 1846, Perth Prison provided specialist housing for those prisoners found ‘not responsible on account of their insanity’, and in 1865 it set up a Criminal Lunatic Department (CLD), with accommodation for 35 males and 13 females; at that time Perth had a total prison population of 600 inmates and 60 staff. In 1881 a separate female lunatics' wing opened, which increased capacity. Offenders were admitted to the CLD because of the potential threat to staff and other prisoners arising from their insanity; however, once admitted, the CLD’s aim was to contain, manage, and treat, men and women with debilitating and dangerous mental disorders, prior to their transfer to an asylum, or discharge and return to society. Other prisons, Dundrum, Ireland, in 1850, and Broadmoor, England in 1863, instigated similar provisions and criminal lunatics became part of an integrated system, rather than anomalies in both justice and health care. However, in Scotland Perth was the only such facility in Scotland until The State Institution for Mental Defectives (now The State Hospital) opened at Carstairs, Lanarkshire, in 1948.

Wording of the 1913 Mental Deficiency Act was representative of accepted terminology at that time and included labels such as 'idiot', 'imbecile', 'feeble-minded' and 'moral imbecile'. It should be noted that this influential act also made it possible to institutionalise women with illegitimate children if they were in receipt of poor relief. Such deleterious terminology continued for decades to come.

During World War One, over 3,000 British and Commonwealth soldiers were found guilty of cowardice by British court marshals, and over 300 were executed, even though most were clearly suffering from what was then commonly known as ‘shellshock’. Many more soldiers were diagnosed with ‘hysteria’ or ‘neurosis’, the symptoms of which included shortness of breath or chest pains, chronic stomach aches, fainting spells, increased anxiety, substance abuse, or prolonged feelings of sadness, paranoia, and hopelessness. Often viewed as fake or dramatic and indicative of an individual’s ‘weakness of mind’, these symptoms were considered to be shameful by society and mimicked the legislative antipathy towards mental illness.

During World War One, over 3,000 British and Commonwealth soldiers were found guilty of cowardice by British court marshals, and over 300 were executed, even though most were clearly suffering from what was then commonly known as ‘shellshock’. Many more soldiers were diagnosed with ‘hysteria’ or ‘neurosis’, the symptoms of which included shortness of breath or chest pains, chronic stomach aches, fainting spells, increased anxiety, substance abuse, or prolonged feelings of sadness, paranoia, and hopelessness. Often viewed as fake or dramatic and indicative of an individual’s ‘weakness of mind’, these symptoms were considered to be shameful by society and mimicked the legislative antipathy towards mental illness.

The field of psychiatry changed after WWI as psychiatrists were forced to treat thousands of troops experiencing neuroses resulting from the stress and trauma of war. They began to experiment with new treatments in attempts to address the causes for some previously incurable conditions, such as schizophrenia. Specialist mental health care continued to be administered mainly from hospitals throughout most of the 1900s. In 1914, it was estimated that there were over one hundred thousand patients housed within over one hundred mental institutions around the United Kingdom, the majority of these institutions were built since the mid-19th century.

However, from the 1950s, amidst concerns surrounding the efficacy of existing mental health care, coupled with the introduction of new psychiatric drugs and changing attitudes towards mental health care, new ways of caring for mental health patients were sought. There was also a desire to reduce costs of that care on the public purse.

The Mental Health Act (England and Wales; 1960 Scotland) repealed the earlier Mental Deficiency Acts and advocated 'community care' rather than institutional care, but the act released little funding to implement that desire. The act, which contained the then familiar terms ‘subnormal' and 'severely subnormal' and introduced 'backward' as a descriptive term, stated that patients should only be admitted to mental health institutions on a voluntary basis unless they were viewed as a danger to themselves or to others, in which case they could be 'sectioned'. Under the new act, entry to hospital was to be decided on medical grounds rather than legal terms. There was also some attempt to integrate mental health care with the wider National Health Service (NHS), which had been formed in 1948.

In 1961 the then government declared that the Victorian asylums that rose ‘daunting out of the countryside’ should be closed, and their patients cared for in conventional hospital wards or within the community. In reality, the integration of mental health services into the wider NHS was limited. It took many years for the nation’s asylums to be decommissioned as the question of who should provide community-centred care, and who should cover the costs, remained unanswered.

In Scotland, and with the introduction of the NHS, there had been a realisation of the role of social factors in health and illness, as evidenced in 1953 by RD Laing and colleagues at Gartnavel Hospital, Glasgow, who initiated a project where staff and patients could spend time chatting together informally, practice cooking, and doing art work, all in comfortable surroundings. By emphasising the importance of normal social interaction for recovery, the team began to take apart the ethos of institutional hospital care. In the 1960s, Dingleton Hospital, a mental health facility in Melrose, in the Scottish Borders, was one of the first hospitals to develop a community mental health programme. The hospital developed an innovative therapeutic community, where staff and patients were encouraged to communicate in frank and open discussion to break down traditional barriers between them. The Scottish examples, together with others across the UK, eventually led to the decision to transform mental health care by shifting services from institutions to community settings, though the process was long, protracted, and controversial.

Various governments had been attracted to the policy of community care since the 1950s. The general aim was to deliver a more cost-effective way of helping people with mental health conditions and/or physical disabilities, by removing them from impersonal, often Victorian, institutions, and caring for them in their own homes. By the 1980s, following much publicised scandals of abuse and inhumane treatment of patients in Ely, Reading, and Caterham, amongst others, there was increasing public criticism and concern about the quality of long-term care for vulnerable people. However, there also existed concerns about the experiences of people leaving long-term institutional care and not being provided with any form of aftercare, but simply being left to fend for themselves in the community. Despite the latter concerns, the Tory government of the day was committed to the not new idea of care in the community and, in 1983, it adopted a new policy of care after the Audit Commission published a report called 'Making a Reality of Community Care', which outlined the advantages of domiciliary care. The new policy defined this as a broad range of services offered to support anyone who wanted to remain independent in their own home. In the mid-1980s, many mental health hospitals were closed as part of the much-debated policy of ‘Care in the Community’.

Debate continues into the merits and consequences of these changes and the impact on current mental health policies and provision. Since 2002, NICE has produced over 80 pieces of mental health guidance on clinical, public health and social care topics relating to mental health. A common theme that runs throughout much of its mental health guidance is the need for a multi-agency approach when supporting people experiencing mental health issues. By bringing together different agencies from health, social care, housing, education, employment, and benefits, people with mental ill-health are more likely to be able to access the services they need to lead a normal life. Yet poor mental health remains an important public health challenge and significant mental health inequalities exist in Scotland and the UK. A person’s position in society plays an important part in their mental health, with less advantaged people having greater experience of poor mental health. Depression is one of the most common mental health conditions, with one in ten people in Scotland diagnosed with the illness at some point in their lives. Stressful experiences (including poverty, family conflict, poor parenting, childhood adversity, unemployment or poor access to quality employment, chronic health problems, social isolation and loneliness, and poor housing) occur across the life-course and contribute to a greater risk of mental ill-health if an individual has multiple experiences.

Meanwhile, the executions of WWI soldiers, for desertion and cowardice, remained controversial throughout the twentieth century, and the men were finally awarded posthumous pardons in 2006, following years of campaigning by their families. Campaigners believed that those men executed should be pardoned, as medical knowledge now strongly suggested that those soldiers had suffered from an illness commonly known as shell shock, which is now recognised as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Prior to the 1970s, anyone who broke down and suffered long-term effects of trauma, including shell shock, was considered constitutionally vulnerable or the product of a degenerate family; in either case,

responsibility lay with the individual. During the 1970s, a paradigm shift occurred in the way that psychological trauma was conceived and managed. Focused research into military personnel led to the formal recognition of post-traumatic stress disorder, PTSD, in 1980. This diagnosis filled an important gap in psychiatric theory and practice, and marked a significant change in the way that trauma was recognised when the etiological agent was outside the individual (i.e., a traumatic event) rather than categorised as an inherent individual weakness (i.e., a traumatic neurosis). Once identified, the definition of PTSD was extended beyond military trauma to include many more forms of traumatic experiences, including illness, sexual, emotional and mental abuse, addictions, bereavement and loneliness. Following this intellectual evolution, more effective modes of treatment and care of people suffering from trauma were researched and implemented, some of which failed whilst others succeeded.

Today, mental health care in Scotland comprises a wide range of medical and psychological therapies, often delivered within a holistic framework and involving both patient and family. The focus has shifted from a narrow concern with the treatment of ‘mental illnesses’ to an emphasis on the promotion of mental health and wellbeing. Local authorities have specific duties to people with mental health issues and can help individuals to access a range of services after a community care assessment. In theory, many people who want help for a mental health problem can get the help they need within their community through either their GP or a community health team, and lots of third sector organisations offer support for people with specific or general mental health conditions. Local associations for mental health might be able to provide a list of groups, as might some national groups.

Unfortunately, few people experience swift or complete recoveries after receiving primary care provision from medical and psychiatric services, and many people find themselves at a loss as to how to further progress positive mental health. This is where local support groups and organisations, such as GRACE, can offer crucial aftercare support through a range of services and activities.

Throughout history, cultures have sought to treat or cure mental ‘maladies’, often devising treatments and techniques now considered to be barbaric. This includes trephination, exorcisms, and bloodletting. In the 19th and 20th centuries, forced isolation from families, friends, and communities might be accompanied by new forms of treatments, including: lobotomy and other forms of psychosurgery; Freudian therapeutic techniques, such as the ‘talking cure’; antipsychotic drugs and other medications; and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), more commonly known as ‘electroshock’. It has been argued that many of these treatments were introduced as a way to fix society’s perception of people with mental illnesses, rather than to help the patients. However, invasive treatments such as lobotomies started to be viewed as morally wrong and they were eventually stopped. Other similarly unpopular treatments evolved to become more effective and less harmful. For instance, ECT continues to be used to treat severe cases of mood disorders, with some patients claiming that the modern version of ECT is the most effective treatment for disruptive mental illness symptoms.

Here is a brief introduction to a few of the other actions, remedies, and techniques used to treat or restrain patients.

One of the earliest known forms of treatment for mental illness, ‘trephination’, or ‘trepanation’, involved opening a hole in the skull using a hand drill, a bore, or a saw. The practice is estimated to have begun around 7,000 years ago, with experts suggesting that this procedure involved removing a small section of skull to relieve severe headaches, mental illness, or demonic possession. Archaeologists have discovered skulls showing scarring from trephination, with the holes and injury to the skull healed, which proves that at least some patients did survive and heal after this type of surgery.

A similar procedure, called a craniotomy, today uses modern techniques to treat bleeding between the inside of the skull and the surface of the brain, conditions usually caused by a physical head trauma or injury. The piece of skull is replaced as soon as possible

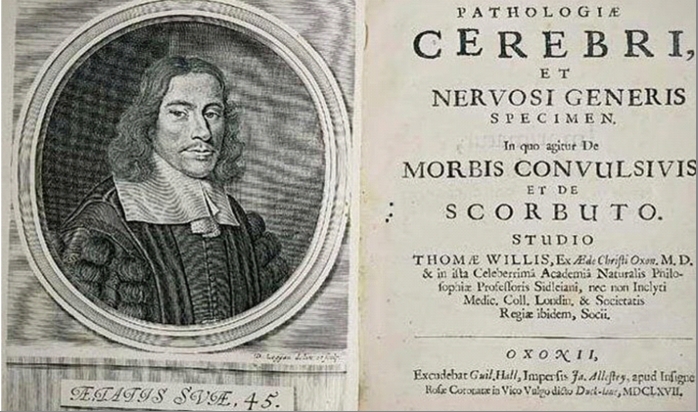

Cover of Thomas Willis' ''Pathologiae cerebri et nervosi generis specimen'' (1667)

The ancient Greek physician, Hippocrates (460 BC–370 BC), is often credited with developing the theory of the four humors, which are all fluids: blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm, and their control on the body and its emotions. When out of balance, the humors were said to have resulted in a range of physical and mental disorders. English physician Thomas Willis (pictured on the previous page) adapted this approach, arguing that an internal biochemical relationship was behind mental disorders. It was believed that bleeding (using blades or leeches), and purging (causing the patient to defecate or vomit to clear the stomach and intestines), would help to restore the balances and heal physical and mental illness. These treatments were accompanied by encouragements to change to lifestyles, diet, and occupation, and to take certain medicines.

A cleric casts out the evil spirit. Image of engraving: Prisma Archivo/Alamy

As noted earlier, historical beliefs about the causes of mental illness, severe depressions, epilepsy, schizophrenia, and other mental disorders were said to be signs of demonic possession in some cultures. As a result, mystic rituals such as exorcisms, prayer, and other religious ceremonies were sometimes used to alleviate individuals, their families and communities of the suffering caused by these disorders. Early Christians believed that madness was a punishment from God and, according to readings of the New Testament, Jesus performed many exorcisms, and commanded others to do the same. This resulted in many painful, sometimes fatal exorcisms of people experiencing mental ill health.

The use of restraints was widespread in 18th and 19th century madhouses and asylums, where attendant staff were often ill-trained and resorted to restraints to maintain order and calm. It was not unknown for patients to be kept in restraints for most of the day. The practice is said to have its roots in the custodial nature of some early asylums, where the purpose was to separate ‘internees’ from the wider public, though in prisons, straitjackets were sometimes also used to punish or torture inmates.

Stated justifications for the use of restraints included:

Leather restraint belt and cuffs. Science Museum Group Collection

Critics abhorred the use of restraints, saying that they demoralised and brutalised both staff attendants and patients, and that the force sometimes used by attendants to restrain uncooperative patients only increased the level of violence in the asylum.

Restraint collar from the 1800s. Science Museum Group Collection

Violent or suicidal patients were sometimes locked in a padded room, or cell, with the intention of calming them down and preventing them from harming themselves or anyone else. They might also be dressed in a straitjacket if they were at risk of self-harm. The length of time that patients were kept in a padded cell varied greatly, with some remaining there for several days. The cells were special rooms with padded walls and round corners to ensure that nothing sharp or dangerous was within reach of patients. Padded rooms, no longer called ‘cells’, are still used today, both in hospitals and police stations.

One of the few psychiatric treatments to receive a Nobel Prize, the lobotomy was the first psychiatry treatment designed to alleviate suffering by disrupting brain circuits that might cause symptoms.

Lobotomies were typically carried out on patients with schizophrenia, severe depression, or Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD), but also, in some cases, on people with learning difficulties or experiencing problems controlling aggression.

More than 20,000 lobotomies were performed in the UK between the 1940s and the 1970s. While a minority of people saw an improvement in their symptoms after lobotomy, most of those that survived the procedure were left stupefied, unable to communicate, walk or feed themselves. Some developed an enormous appetite and gained considerable weight. Seizures were a common complication of surgery. The purpose of the operation was to reduce the symptoms of mental disorders, but experts soon realised that the procedure was not effective enough to justify the risks. Nonetheless, it took years for the medical profession to formally acknowledge that the negative results outweighed the benefits, and to accept that drugs developed in the 1950s were more effective and much safer.

In the 1930s some patients were deliberately put into low blood sugar comas to treat mental illness, as it was believed that dramatic changes to insulin levels altered wiring in the brain. Originally developed in the 1920s, insulin coma therapy was based on the idea that patients could be jolted out of an episode of mental illness. The therapy would last several weeks or months, with patients receiving daily insulin injections to induce a coma-like state; this was then reversed after an hour or so with an injection of glucose. The insulin dosage was increased every day, inducing increasingly deeper states of unconsciousness until the patient was at ‘maximum benefit,’ at which point they would be weaned off the insulin. This process was repeated again and again, with patients usually receiving between thirty to fifty insulin comas. Although there was never any evidence that the treatment worked, many practitioners swore by it, and the practice continued into the 1960s.

A mental hospital patient receiving insulin coma therapy

Patient receiving general electric treatment during WW1

Prior to the development of electroconvulsive therapy, or ECT for short, patients with mental ill-health might be deliberately induced to have seizures by using drugs such as the stimulant, Metrazol. As the understanding of mental illness evolved, some practitioners used this therapy to also relieve other conditions, such as epilepsy and schizophrenia. These drug-induced seizures were not effective, nor were the outcomes of the treatments. However, this field of seizure-related therapies later led to the more effective study of electric shocks and ECT.

Water therapy, or hydrotherapy, used as an effective treatment for both physical health and wellbeing is long established across space and time and archaeologists have discovered many examples of ancient spas and pools that once offered water therapies. However, one of the 19th century inventions was shock hydrotherapy: the method of using water to treat madness. Similar methods had been used as early as the 17th century, with patients then being forcefully plunged into cold ponds or the sea in the belief that water could halt excessive violent and irrational moods and actions. Unfortunately, patients sometimes drowned and the outdoor practice did not become popular. This changed with the coming of modern plumbing; large psychiatric hospitals were built with indoor technologies to deliver hydrotherapy as a way of targeting the body to treat the mind, and it took on a greater variety of forms.

Rather than exposing the whole body to water, by the turn of the 19th century, physicians were focusing on the brain as the site of madness, and they started directing cold showers onto patients’ heads to ‘cool their hot brains.’

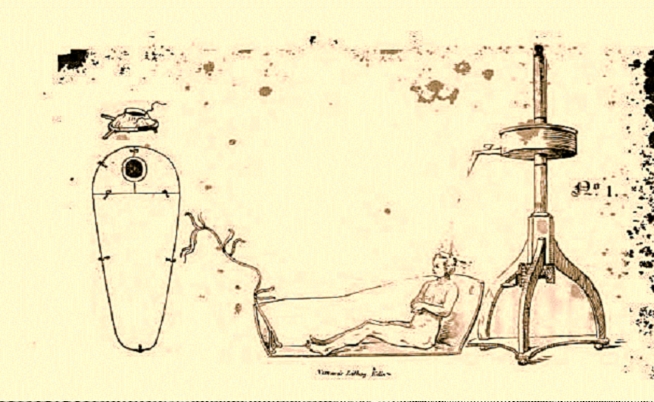

Alexander Morison’s apparatus for giving the douche (Morison / Internet Archive)

The method originally required nothing more complicated that having an attendant pour water over the head of a restrained patient. As time passed, physicians devised more elaborate mechanical showers. The Scottish physician, Alexander Morison, created a douche that resembled a pod, in which a patient sat with their head sticking out of a hole in the top. Water was then steadily poured down onto the patient’s head from above. Other devices were designed, all with the aim of producing shock and fear as a means of treating the mental illness.

Warm water therapy was introduced later, with hospital staff placing patients into warm baths that lasted hours or even days. The patients were first wrapped tightly in wet sheets, then in a rubber sheet and left to sweat for hours, before being placed in a warm bath. Doctors believed that such therapies relieved congestion in the brain, thereby eliminating toxins that cause insanity.

Today, both cold and warm water hydrotherapies are widely used as alternative therapies to treat all manner of musculoskeletal conditions, including lumbar pain, arthritis, and fibromyalgia. Soaking in water is recognised to reduce swelling and inflammation and also provides support for sore limbs; this ease of pressure helps to also increase circulation, which promotes healing. The benefits of this therapy extend beyond the biological effect, as it lowers heart rate, slows breathing and relaxes the body, and helps to improve mental health.

Source: https://search.findmypast.co.uk/search-world-records/scotland-mental-health-institutions-registers-and-admissions.

N.B. Many asylums and facilities changed their names repeatedly. For example, Gartnavel Royal Hospital, Glasgow, first opened as the Glasgow Lunatic Asylum. After it received a royal charter in 1824, it became the Glasgow Royal Lunatic Asylum. In 1931, it was renamed the Glasgow Royal Mental Hospital, and in 1963, it adopted its present name.